Anthony C. Acevedo’s four children and two grandchildren escorted his flag-draped coffin as he came to rest at Riverside National Cemetery before the Prisoner of War Missing in Action Memorial.

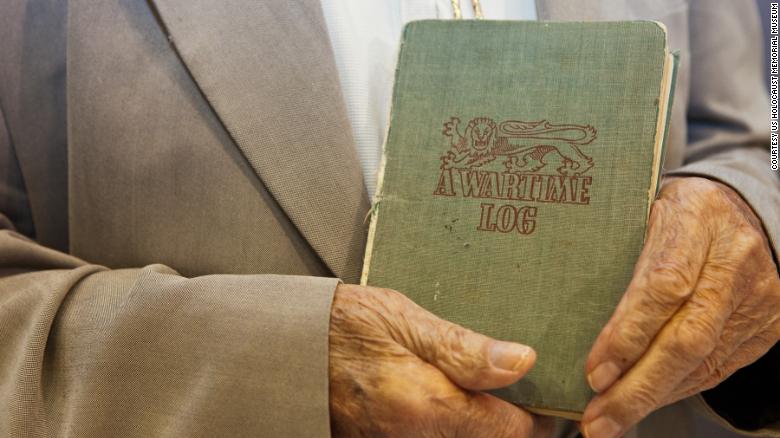

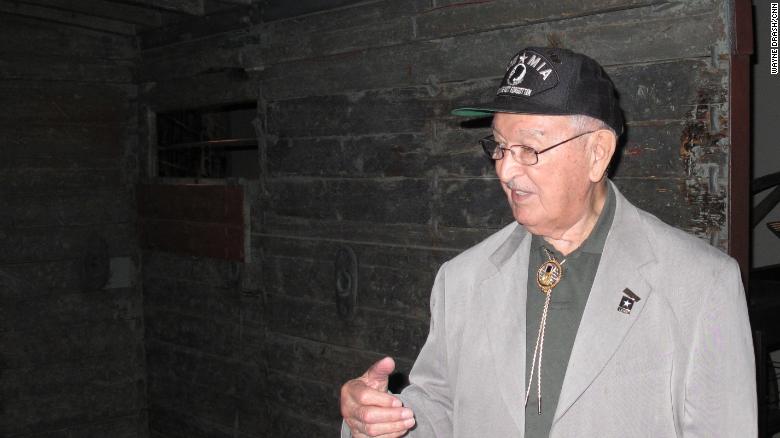

Acevedo was a World War II medic and one of 350 US soldiers held in a Nazi slave labor camp. His journal proved critical in documenting the deaths and atrocities inside the camp.

He would become the first Mexican-American ever recognized as a Holocaust survivor. He kept one brutality secret, though, until the final months of his life.

“Not only is he a great American, but he’s also an icon,” Col. Dan Forden, a chaplain at the VA Hospital in Loma Linda, told the crowd. “He’s the real measure of a man — this is the man we want to be.”

Three rifle volleys echoed across the hushed crowd. A bugler played “Taps” as veterans gave Acevedo one final salute. Each of Acevedo’s children were presented with folded flags, including the one from his coffin, before a bagpiper played “Amazing Grace.”

“If I can describe my father with one word, it would be heart,” Acevedo’s daughter, Rebeca Acevedo-Carlin, said at an earlier memorial service.

“What an incredible, genuine man he was,” said his son, Fernando Acevedo. “He would always say have faith, care for others and, more importantly, love one another. I saw my father act with love toward everyone.”

His story is one of bravery, honor and heroism — one forever etched in American history.

Among the ‘undesirables’

Anthony Claude Acevedo was born July 31, 1924, in San Bernardino, California, to parents who had entered the country illegally from Mexico. The young family moved to nearby Pasadena, where Acevedo attended segregated schools with blacks, Asians and other Latinos. When his parents were deported back to Mexico in 1937, he went with them.

But his love for America never wavered. After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Acevedo was determined to defend his homeland. At age 17, he crossed back into the United States and enlisted in the Army. He received medical training in Illinois and eventually landed in the European theater in October 1944, where he served as a medic.

“Was captured the 6th of January 1945,” he wrote in his first journal entry after being taken prisoner at the Battle of the Bulge.

The next month, 350 US soldiers — Jews and “undesirables,” including Acevedo — were separated from other prisoners of war. They were told they were going to a beautiful camp with live shows and a theater. Instead, they were put on cattle cars and transported to Berga, a slave labor subcamp of the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany where tens of thousands of Jews died.

The US soldiers worked 12-hour days in the final weeks of the war, digging tunnels for a sophisticated V-2 rocket factory. Soldiers were starved and brutalized with rubber hoses and bayonets. Some were fatally shot in the head with wooden bullets. The Nazis forced Acevedo to fill the holes in the heads of his fellow soldiers with wax to cover up the killings.

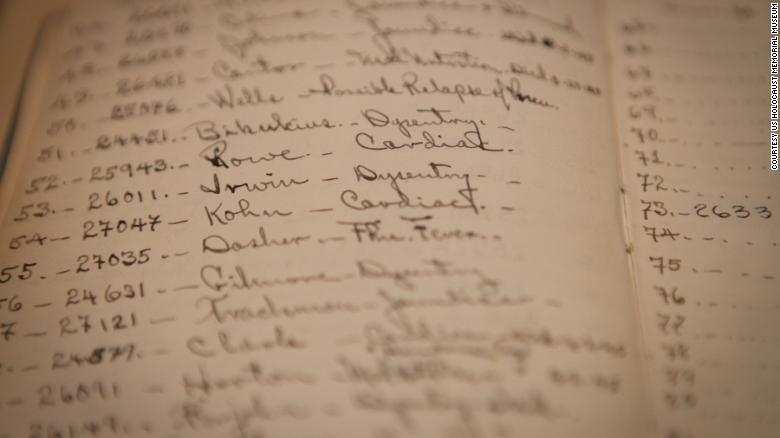

Acevedo used a fountain pen to record the atrocities in a diary, noting every US sol

dier’s death that he saw. About half of the soldiers sent to Berga survived, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

During the next six decades, the US government never acknowledged its soldiers were held in a slave labor camp. But after Acevedo shared his account with CNN in 2008, the story went viral and the public demanded answers. Then-US Reps. Joe Baca of California and Spencer Bachus of Alabama pressed then-Army Secretary Pete Geren to recognize the soldiers.

Within months, Army Maj. Gen. Vincent Boles met with six Berga survivors at a POW event in Orlando, presenting them with flags flown over the Pentagon and honoring them for their sacrifice. One soldier received the Bronze Star, one of the nation’s highest medals.

“It wasn’t a prison camp. It was a slave labor camp,” Boles told them. “You were good soldiers and you were there for your nation.”

Acevedo boycotted the ceremony, saying he felt it should have been held in Washington.

A ‘moral obligation’

In 2010, Acevedo became the first Mexican-American to register as a Holocaust survivor at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, out of 225,000 registered there. Acevedo donated his diary, Red Cross medic’s band, cross and prayer book to the museum.

The museum recorded his oral history in English and Spanish. After Acevedo came forward, other Berga survivors did the same, recording their testimonies and donating historical artifacts. Previously, the museum only had a handful of testimonies from Berga; now it could add their stories to its permanent collection.

“We were able to finally tell their story in our exhibition for the first time because we now had physical evidence that we could show our visitors,” said Kyra Schuster, a museum curator.

Acevedo’s story also allowed Mexican-Americans to connect to the Holocaust in a way they never had before. Schuster still travels the country telling the story of Berga, and she says it’s always incredible when Latinos learn of Acevedo’s survival and courage.

When asked why he put his own life at risk by keeping a diary of every US soldier’s death he witnessed, Acevedo told the museum, “It was my moral obligation to do so.”

“That’s always stuck with me,” Schuster says, “because I think that defines who he is.

“He was this man who, despite the odds against him, despite what he was going through and experiencing, it was still important for him to take care of others, to document what was happening, to make sure the world knew what had happened to them.

“That’s why he spoke out later in life. He was always putting other people ahead of himself. That’s how I see him, and that is so admirable.”

Proud of his heritage, Acevedo listened with dismay over the last year as the nation’s leaders took a hardened stance toward immigrants.

“They don’t know shit from Shinola,” Fernando Acevedo recalled his father saying.

His son said Acevedo, a lifelong conservative, would shake his head and change the TV channel from politics to Westerns. He’d then tell Fernando: “Always remember: Never repay evil with evil. Remember what my buddies and I went through. Never treat anybody like they’re below you. We can’t turn a blind eye.”

After the war, Acevedo, then 20, returned home and worked as a surgical technician in an ear, nose and throat clinic in Pasadena. Around that time, he took a trip to Durango, Mexico to visit his father — who didn’t believe his account of being held in a slave labor camp. “You’re a coward for allowing yourself to be captured,” his father told him. “You should’ve killed yourself.”

Acevedo left his father’s home the next day with only a duffel bag and set off on his own. The two didn’t speak for years. On the train ride back to California he met the woman of his dreams. Eight months later, he and Amparo Martinez were married. Together, they had four children: Tony, Rebeca, Fernando and Ernesto.

Acevedo settled into a successful aerospace engineering career, working for North American Aviation, McDonnell Douglas and Hughes Space and Communications, where he retired in 1987 after 35 years as a design engineer.

In retirement, the demons of war resurfaced. He would break into a sweat four to five times a day, shaking and trembling as he relived his captivity. At night, he was haunted by nightmares so intense his muscles would constrict and he’d wake up screaming.

He’d relive seeing a fellow medic killed by machine gun fire. Germans would shove him with bayonets. A dead comrade would suddenly flash into his mind.

To help cope, he volunteered at the VA hospital in Loma Linda. He said he liked spending time with the veterans there because so many died alone. He would share his story with local high school students and was buoyed by his work with the Holocaust museum.

“He was the epitome of kindness,” Fernando said. “We should all be that way for fellow man — this power of strength yet gentleness to give to others. That was my dad’s mission.”

‘Many of our men died’

A corporal, Acevedo served as a medic for the 275th Infantry Regiment of the 70th Infantry Division. Surrounded by Nazis at the Battle of the Bulge, he was captured after days of brutal firefights. He saw one of his fellow medics, Murray Pruzan, gunned down.

“When I saw him stretched out there in the snow, frozen, God, that’s the only time I cried,” Acevedo once told CNN. “He was stretched out, just massacred by a machine gun with his Red Cross band.

“You see all of them dying out there in the fields. You have to build a thick wall.”

Acevedo was first taken to a prison camp known as Stalag IX-B in Bad Orb, Germany, where thousands of American, French, Italian and Russian soldiers were held as prisoners of war. He would be known by the Germans as Prisoner No. 27016.

One day, he said, a German commander gathered the US prisoners and asked all Jews “to take one step forward.” Few willingly did so. Jewish soldiers wearing Star of David necklaces began yanking them off.

About 90 Jewish soldiers and another 260 US soldiers deemed “undesirables” — those who “looked like Jews” — were selected. Acevedo, who was Catholic, was among them.

“They put us on a train, and we traveled six days and six nights. It was a boxcar that would fit heads of cattle,” he said. “They had us 80 to a boxcar.”

It was February 8, 1945, when they arrived. The camp was known as Berga an der Elster. The soldiers, Acevedo said, were given 100 grams of bread per week made of redwood sawdust, ground glass and barley. Soup was made from cats and rats.

If soldiers tried to escape, they would be shot and killed. Any who were captured alive would be executed with gunshots to their foreheads, Acevedo said.

“Many of our men died, and I tried keeping track of who they were and how they died,” he said. “I’m glad I did it.”

The names and dates of death were logged in his diary as the days wore on.

32. Hamilton 4-5-45

33. Young 4-5-45

34. Smith 4-9-45

35. Vogel 4-9-45

36. Wagner 4-9-45

The main Buchenwald camp was officially liberated on April 11, 1945. But as US troops neared, Nazis emptied the camp and its subcamps of tens of thousands of prisoners and forced them to march. The soldiers held at Berga were no exception.

“Very definite that we are moving away from here and on foot,” Acevedo wrote in his diary on April 4, 1945. “This isn’t very good for our sick men. No drinking water and no latrines.”

The soldiers’ death march would last three weeks and stretch 217 miles. Acevedo pushed a wooden cart with the bodies of the dead and sick stacked on top of each other. Toward the end of the march, there were as many as 20 bodies on the cart.

“We saw massacres of people being slaughtered off the highway. Women, children,” he said. “You could see people of all ages hanging on barbed wire.”

On April 13, 1945, Acevedo wrote of the soldiers’ patriotism, even as they were being marched to their graves. “Bad news for us. President Roosevelt’s death. We all felt bad about it. We held a prayer service for the repose of his soul.”

His entry that day ended with: “Burdeski died today.”

Acevedo kept his diary hidden in his pants. He mixed snow or urine with the ink in his fountain pen to make it last.

US troops liberated Acevedo and the remaining prisoners from the Nazis on April 23, 1945. Before returning home, Acevedo signed a US government document that haunted him for decades:

“You must give no account of your experience in books, newspapers, periodicals, or in broadcasts or in lectures,” it said. “I understand that disclosure to anyone else will make me liable to disciplinary action.”

He had shared his story with students locally for years and had spoken to a couple of authors who wrote books on the Berga soldiers. He decided to speak with CNN in 2008 to make sure the story was preserved in the internet age. “Let it be known,” he said. “People have to know what happened.”

The government said the document wasn’t meant to keep the men silent — that it was meant to protect sources in Germany who helped aid liberating troops. Acevedo had a one-word response to that explanation: “Hullabaloo.”

‘This is how low man can get’

The Nazi camp commanders at Berga — Erwin Metz and his superior, Hauptmann Ludwig Merz — were tried for war crimes in Germany in 1946.

They gave a much different account of treatment at Berga. They said US prisoners ate better than the guards, had comfortable accommodations and that the Nazis tried to help the Americans as best they could. Surviving US soldiers were not called to testify.

Merz described inspecting the soldiers on April 19, 1945, two weeks into the death march. “Roughly 200 prisoners were there, all of whom gave the appearance of being well-rested,” Merz told the court. “I noticed one sick, who was sitting on the ground, because he could not stand up the entire time it took me to make my inspection.”

Pressed further, he said, “Among those that I saw, there were no sick except the one I mentioned.”

Acevedo’s diary entry from that same day painted a different picture: “More of our men died today, so fast that you couldn’t keep track of their numbers.”

Merz and Metz were found guilty and sentenced to die by hanging. But in 1948, the US government commuted their death sentences, and in the 1950s, the men were set free.

In explaining its decision, the War Department said, “Metz, though guilty of a generally cruel course of conduct toward prisoners, was not directly responsible for the death of any prisoners except one who was killed during the course of an attempt to escape.”

I once asked Acevedo about his feelings toward Metz. He wept for 10 minutes as his muscles tightened and his breathing grew strained, the throes of post-traumatic stress overtaking him. I held him in my arms and told him how much his country loved him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, gasping. “I’m sorry. I want to say more, but I can’t.”

This past December, Acevedo was hospitalized with heart problems. His son, Fernando, was searching through his father’s military records when he found a psychiatric evaluation from 1996. Fernando’s heart sank as he read through the file. Suddenly, everything made sense — his father’s tremors, his waking in the middle of the night, his screams.

The evaluation detailed a war crime his father could not speak about with his son:

“He was raped while the Germans laughed and became sexually aroused,” the file said. “He was humiliated and felt violated and infinitesimal, like a toy, not a human being. Veteran had extremely traumatic experiences in combat and in the hands of the Gestapo who were ruthless in their methods.”

When his father returned from the hospital, Fernando sat him down and showed him the file.

“Oh,” his father said. “I’m glad you found it.”

Fernando said his father paused before continuing: “I want you to tell everyone what I went through and how I struggled with the nightmares. I want you to tell everybody.”

Acevedo told his son to include the rape in his obituary so the world can understand: “This is how low man can get.”

Filled hallways and one final salute

Acevedo took his final breath at 6:28 p.m. on February 11, in the same VA hospital where he’d spent the last two decades volunteering.

His body was draped in a US flag and prepared for a traditional honor walk, a way to treat a veteran’s death with dignity. Word spread throughout the hospital that the beloved Acevedo — whose warmth and love cheered up veterans, doctors and nurses alike — was gone.

Hallways overflowed with people standing at attention as Acevedo was accompanied by his four children.

“They saluted my dad all the way up and down the hallway as we were walking. Four floors like that,” Fernando said. “Nurses, doctors, patients who were able to stand — everyone was standing at attention saluting my dad.”

“I tell you, that was really heavy.”

Acevedo died with a clear conscience, having told the world about the treatment he and his fellow soldiers at Berga faced. His message was one of love and peace.

As he was put to rest Thursday, I couldn’t help but think of his giant smile and gentle voice. “You only live once. Let’s keep trucking. If we don’t do that, who’s going to do it for us? We have to be happy. Why hate?” he once told me.

A true national treasure.